Eye For Film >> Movies >> Dr. Delirium And The Edgewood Experiments (2022) Film Review

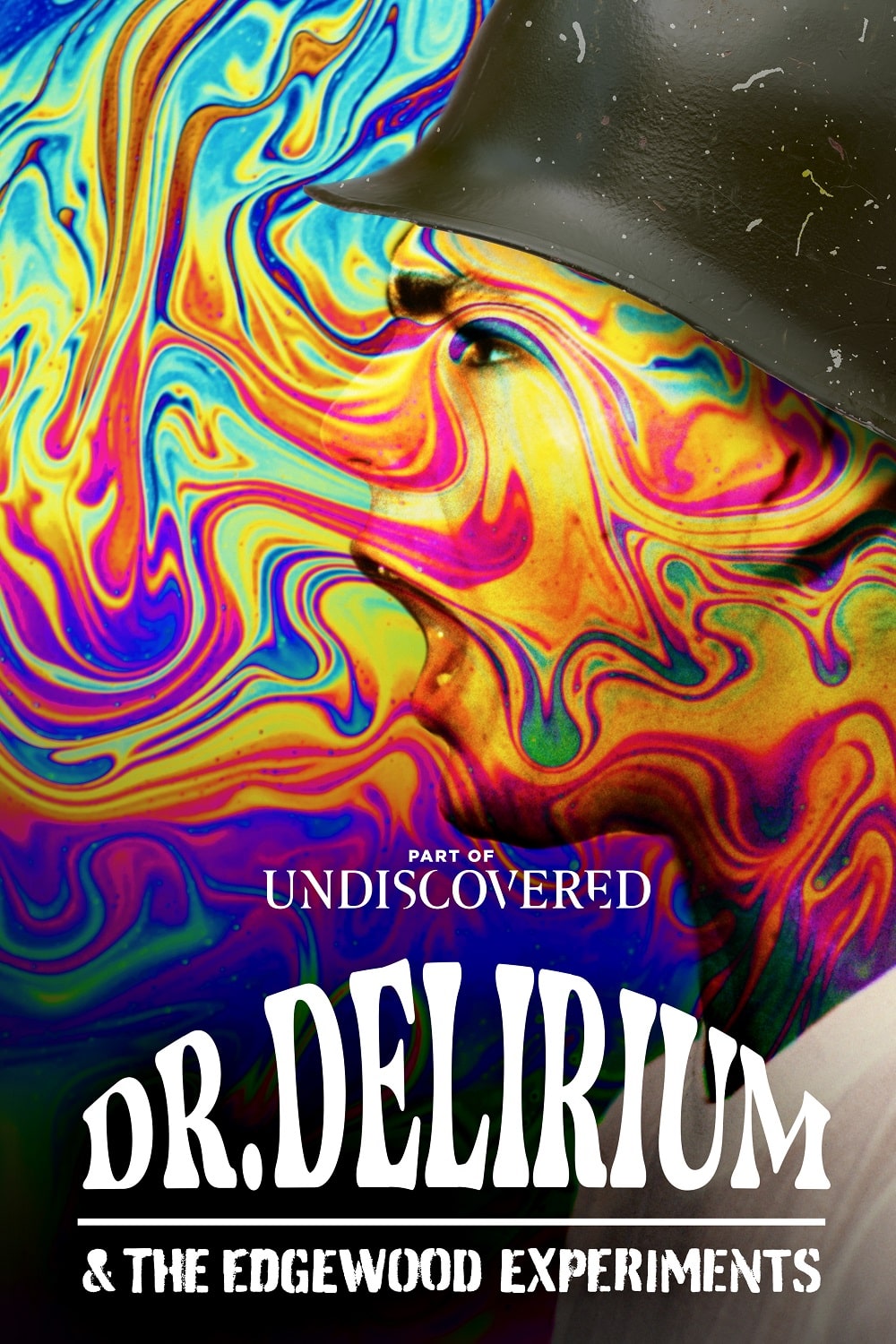

Dr. Delirium And The Edgewood Experiments

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

These days most people are aware that the US military went through a period of testing experimental psychotropic weapons on its own soldiers, but though the later excesses of MK Ultra are fairly well documented, some of the earliest testing programmes, initiated in 1955, remain shrouded in mystery. This documentary sets out to change that, exploring the 20 year series of tests conducted at Edgewood Arsenal under the supervision of research director James Ketchum, who, in a never-before-seen interview, takes on the critics and explains why he still feels he was right to undertake this work.

Given its title, you might not expect the film to offer him a very sympathetic hearing, and you would be right. Although he’s given the opportunity to explain why he didn’t feel that he was in breach of ethical codes, this is framed in a hostile way. It’s difficult to know what might have been left out of the interview, but it’s unfortunate that there is no-one present to explain why the research was thought to be necessary from a military perspective, and no mention is made of the similar large scale programmes underway at the time in the Soviet Union, which risks giving the impression that there was no defensive aspect to the work and that it was much more about experimentation for the sake of it than was really the case.

Alongside the absence of military perspective is a distinct absence of scientific perspective, and this weighs in the other direction. Although it is noted that doses of experimental chemicals given to test subjects (human and otherwise) were not very well measured or recorded, this is treated first and foremost as reason to worry about the effects on those individuals, with little to draw viewers’ attention to the fact that it effectively invalidated some of the experiments and therefore meant that the men suffered for nothing.

On the flip side, discussions around the meaning of full and informed consent do not reference the impossibility of describing potential long term effects of drugs which were so new, or look at how more ethical practitioners deal with such difficulties in, say, medical research. The argument that it would be impossible to stop such experiments once they were underway completely ignores measures which might have been taken to mitigate distress, such as providing a calming environment or administering the marijuana whose effects were well understood at the facility because its own potential use in warfare had been studied there previously.

Most of the material here focuses on two drugs: LSD, which may be personally familiar to some viewers but was used in this instance in much higher doses, and BZ, the actually cause of the delirium referenced in the title, which is used today as an anti-cholinergic to treat problems like urinary incontinence in the elderly – again in much smaller doses. The trauma associated with the latter is significant and well established here, and it is sensibly emphasised that there has never been a market for it as a recreational drug.

The interview with Ketchum – fascinating insofar as it goes – is accompanied by round table discussions with several of the men who volunteered for the original testing programme, who discuss exactly what they were told before getting involved, and why they thought it sounded like an easy gig. Nobody asks them why they stuck around after repeated bad experiences, so whether or not they had the option of dropping out is never established. Their testimony is moving but only briefly provides specifics about the long term problems which some of them have suffered as a result. There is a balance to be struck here with regard to the men’s privacy, but given the amount of weight which the film attaches to these long term issues, the amount which viewers are expected to take on trust is problematic.

Though it references other activities later conducted by MK Ultra, this film does so only briefly, perhaps due to concerns that its subject matter just doesn’t seem very exciting by comparison. This is fair enough – there are some seriously wild stories to be told about those activities, to the point where the research directors’ ability to continue attracting funding leaves one wondering why they felt they needed drugs to help them control others’ minds – even if it does rob the narrative of a proper ending. The real strength of this film, aside from the Ketchum interview, is the amount of archive footage it includes. Some of this has been used before elsewhere and some bits, curiously, are repeated, but it’s still very effective in capturing the mood of the time.

With a more incisive approach and less time wasted on patronising reaction shots, this could have been a really strong film. As it is, it’s problematic in many of the same ways as the original research – poorly organised and subject to bias – but it still supplies interesting detail for those familiar with the subject and may provide a gateway through which others can begin discovering a fascinating history with ongoing relevance today.

Reviewed on: 09 Jun 2022